The report examines three causes of racial disparity in imprisonment and presents a series of promising reforms from over 50 jurisdictions across the country that can mitigate their impact.

Related to: Incarceration, Racial Justice, Sentencing Reform

This publication is the third installment in The Sentencing Project’s “One in Five” series examining racial inequities in America’s criminal legal system. Click here to read the complete four-part series.

As noted in the first installment of this One in Five series, 1 scholars have declared a “generational shift” in the lifetime likelihood of imprisonment for Black men, from a staggering one in three for those born in 1981 to a still troubling one in five for Black men born in 2001. 2

The United States experienced a 25% decline in its prison population between 2009, its peak year, and 2021. 3 While all major racial and ethnic groups experienced decarceration, the Black prison population has downsized the most. 4 But with the prison population in 2021 nearly six times as large as 50 years ago and Black Americans still imprisoned at five times the rate of whites, the crisis of mass incarceration and its racial injustice remain undeniable. 5 What’s more, the progress made so far is at risk of stalling or being reversed.

This third installment of the One in Five 6 series examines three key causes of racial inequality from within the criminal legal system. While the consequences of these policies and issues continue to perpetuate racial and ethnic disparities, at least 50 jurisdictions around the country—including states, the federal government, and localities—have initiated promising reforms to lessen their impact.

Causes: Extreme sentences for violent crimes and reliance on criminal histories as a basis for determining prison sentences are drivers of racial disparities in imprisonment. In addition, the punitive nature of the War on Drugs and the associated sentencing laws that it sprouted, including mandatory minimum sentences, crack-cocaine sentencing disparities, drug-free school zone laws, and felonization of drug possession disproportionately impact Black Americans.

Remedies: Various jurisdictions have reformed laws with disparate racial impact. For example, Washington, DC, allows many incarcerated people who have already served 15 years to petition the courts for resentencing, helping to curb extreme prison terms. Pennsylvania’s sentencing commission has proposed scaling back the impact of criminal histories on sentencing guidelines. The federal government narrowed the crack-cocaine sentencing disparity in 2010 and applied it retroactively in 2018. Alaska, California, Connecticut, Oklahoma, and Utah have reduced prison admissions with de-felonization statutes that downgrade drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor.

2. Racial bias influences criminal legal practitioners’ use of discretion.

Causes: As discussed in installment two of the One in Five series, communities of color are over-policed through biased traffic stops, pedestrian searches, and drug arrests. 7 In addition, prosecutors and judges often treat Black and Latinx people more harshly in their charging and sentencing decisions. Bias also affects the work of juries, correctional officers, and parole boards. Police and prosecutors, via their unions and professional associations, often lobby, litigate, and engage in public advocacy against reforms.

Remedies: Installment two of this series discussed reforms to reduce the footprint of policing. Several jurisdictions have also taken steps to mitigate the impact of bias in discretion throughout the criminal legal process. For example, Arizona is the first state to eliminate peremptory challenges in jury selection, so that prospective jurors cannot be rejected without an explanation. Michigan’s parole board uses evidence-based guidelines to minimize the influence of subjective factors on their decisions. In a growing movement of reform-oriented prosecutors, district attorneys in Los Angeles and Philadelphia are using their discretion to avoid extreme sentences.

3. A financially burdensome and under-resourced criminal legal system puts people with low incomes, who are disproportionately people of color, at a disadvantage.

Causes: Pretrial release often requires cash bail which disadvantages low-income people of color and increases the pressure to take a less favorable plea deal. State indigent defense programs are critically underfunded. In addition, incarcerated individuals struggling with substance use disorders often do not receive the treatment they need, jeopardizing successful reentry. Further, parole and probation supervision imposes scrutiny with few services.

Remedies: Reforms are underway to curb punitive policies that disparately affect people with limited financial resources. Illinois became the first state to end cash bail in 2023, following New Jersey’s major bail overhaul in 2017. District attorneys in jurisdictions including Boston and Manhattan have reduced prosecutions of “crimes of poverty.” Holistic defense models, which provide comprehensive support to individuals and their communities, are available from the Tribal Defense Offices and other communities including Bronx, NY, Oakland, CA, and Houston, TX. New York and California have reduced the footprint of community supervision.

But this progress is under threat. For example, Washington, DC’s Mayor has sought to limit resentencing opportunities under the District’s second look law. 8 Drug arrests remain high across the country and Oregon’s struggle implementing its drug-decriminalization program has sparked calls for the policy’s reversal. 9 Backlash against reform-oriented prosecutors has led to recalls, litigation, and legislative attacks in California, Georgia, Florida, and Pennsylvania. 10 Crime concerns have also fueled misdirected pushback against bail reform in California and New York, and supported a reversion to enforcing “crimes of poverty” in Baltimore. 11

Tackling the above noted sources of disparity would not fully eliminate racial inequity in incarceration. Also needed, as discussed in the second installment of this series, are durable investments in communities of color that are disproportionately impacted by serious violent crime, as well as a reduction in the footprint of policing. 7 In addition, policymakers will need to tackle a fourth driver of disparity which will be examined in the final installment of this series: Criminal legal policies that exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities.

Like an avalanche, racial disparity accumulates as people traverse the criminal legal system. The roots of this disparity precede criminal legal contact: as examined in the second installment of this series, conditions of socioeconomic inequality contribute to higher rates of serious crimes among certain populations of color. 7 But the criminal legal system exacerbates this underlying disparity. As a comprehensive scholarly review conducted by the National Academies of Sciences explains: 14

Blacks are more likely than whites to be confined awaiting trial (which increases the probability that an incarcerative sentence will be imposed), to receive incarcerative rather than community sentences, and to receive longer sentences. Racial differences found at each stage are typically modest, but their cumulative effect is significant.

This report presents an overarching framework for understanding the sources of disparity from within the criminal legal system. The first two drivers of disparity relate to race: disparate racial impact of laws and policies, and bias that shapes everyday decisions among criminal legal practitioners. The next source of disparity relates to socioeconomic status and its overlap with race and ethnicity: criminal laws, policies, and decisions often disadvantage people with low incomes, who are disproportionately people of color. The final source of disparity, which will be examined in the next installment of this series, is the criminal legal system’s magnification of disadvantage, through laws and policies that push people deeper into poverty and into the margins of society. These reports will both scrutinize these drivers of inequality and present promising reforms from across the country to mitigate their impact.

| Causes of Disparity | Remedies |

|---|---|

| Lengthy and life sentences are disproportionately levied on Black Americans and other people of color. | Legislatures in California and the District of Columbia are providing second look opportunities for individuals serving excessive sentences that are no longer in the interest of justice. |

| Ostensibly race-neutral sentencing “enhancements” such as for drug-free school zones and gang affiliations disproportionately impact Black and Latinx individuals. | States are acknowledging the limited effectiveness and negative impact of sentencing “enhancements.” Indiana amended its laws aggravating sentences related to drug-free school zones, California limited “enhancements” for gang affiliation, and Virginia discontinued law enforcement’s use of gang databases. |

| Felonization of drug possession and mandatory minimum sentences disproportionately impact Black Americans. | Alaska, California, Connecticut, Oklahoma, and Utah have reduced prison admissions with de-felonization statutes. States and the federal government have repealed or shortened certain mandatory minimum sentences, and created safety valve provisions. |

| Causes of Disparity | Remedies |

|---|---|

| Prosecutors disproportionately enforce habitual offender and mandatory minimum sentencing laws against Black individuals and disparately refuse to divert Black and Latinx people, leading to more punitive sentences for people of color. Prosecutors often lobby and litigate against reforms. | Reform-oriented prosecutors in Los Angeles, Alameda County, CA, and Philadelphia are limiting extreme sentences through their charging decisions and supporting resentencing petitions. Organizations such as Fair and Just Prosecution, For the People, Prosecutors Alliance of California, and Vera’s Motion for Justice are uniting reform-oriented prosecutors and joining forces to support scaling back excessively punitive sentences. |

| Correctional officers, parole boards, and probation and parole officers are more strict towards people of color when making disciplinary assessments and parole eligibility. | States including Idaho, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Missouri are implementing evidence-based guidelines for parole evaluations to help eliminate bias. Maryland joined most other states in ending gubernatorial reviews of parole decisions, reducing potential political influences. |

| Juries display implicit bias towards defendants of color. | Court systems in Iowa and New York are placing an emphasis on increasing the diversity of jury pools and Arizona, California, and Washington have narrowed peremptory challenges in jury selection. California legislators are also empowering judges to reverse the impact of bias. |

| Causes of Disparity | Remedies |

|---|---|

| Criminalizing activities often associated with poverty such as driving without a license, drug use, and prostitution disproportionately impact people of color. | Prosecutors in Baltimore and Boston have reduced the footprint of the criminal legal system by refusing to prosecute “crimes of poverty.” |

| Pretrial detention imposes onerous cash bail requirements and often employs inequitable risk assessment tools. | Illinois and Philadelphia have increased pretrial release by eliminating cash bail and using updated risk assessment tools. |

| Indigent defense programs are chronically under-resourced, leaving clients with inadequate representation or with no representation at all. | New York and Oregon are increasing funding for public defenders and Oregon is enforcing standards of representation for indigent clients. |

| Transitional services and supervision provide insufficient reentry and treatment support and impose overly harsh requirements. | Practitioners in Bronx, NY, Oakland, CA, and in Tribal Defense Offices are helping to expand social services and improve outcomes of justice-involved individuals by engaging in holistic defense practices and narrowing the footprint of onerous probation and parole supervision. |

The next, and final, installment of the One in Five series will explore a fourth source of racial inequality: criminal legal policies that exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities and divert public spending from effective investments in public safety.

Myriad criminal legal policies that appear to be race-neutral combine with broader socioeconomic patterns to create a disparate racial impact. Policing policies that cast a wide net in neighborhoods and on populations associated with high crime rates disproportionately affect people of color, as examined in the second installment of this series. 15 Consequently, people of color are more likely to be arrested even for conduct that they do not engage in at higher rates than whites. This section explains how extreme sentencing and laws that aggravate sentences for certain individuals have a disparate racial impact.

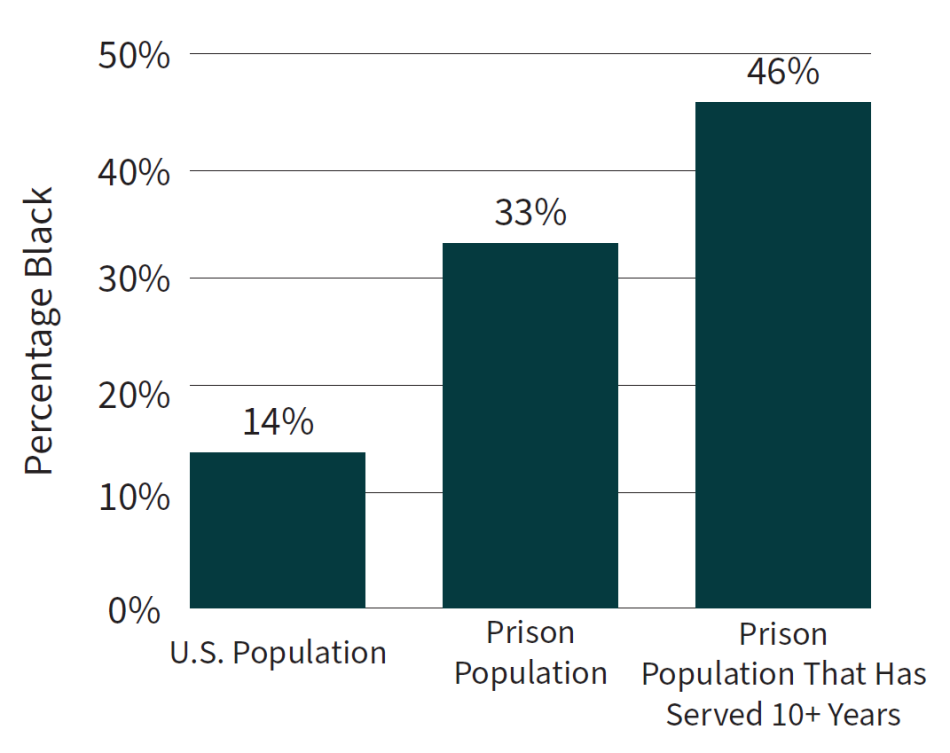

While racial disparities can be found at every sentencing level, they are most pronounced in lengthy and extreme sentences. In 2019, Black Americans represented 14% of the total U.S. population, 33% of the total prison population, and 46% of the prison population who had already served at least 10 years. 16

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates; Carson, E.A. (2020). Prisoners in 2019. Bureau of Justice Statistics; United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. National Corrections Reporting Program, 1991-2019: Selected Variables. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2021-07-15.

Life sentences are also disproportionately imposed on Black, Latinx, and other people of color. More than two-thirds of people serving life sentences are people of color. 17 Among people serving life without parole sentences, 55% are Black. 18 Black Americans also made up one-third of those executed between 1976 and 2022, and are more than 40% of the population on death row. 19

Racial disparities in serious criminal offending contribute to these disparities, as does the fact that white Americans’ association of crime with Black and Latinx people bolsters their support for punitive policies. 20 The disproportionate imposition of extreme sentences on people of color has led the National Academies of Sciences to recommend “establishing second-look provisions for long sentences…and eliminating the death penalty” as a way to reduce racial disparities in incarceration. 21

Laws designed to more harshly punish certain crime patterns or to divert some people from punishment often have a disparate impact. For example, drug-free school zone laws mandate longer sentences for people caught selling drugs in school zones, such as within 1,000 feet of school property. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have some form of drug-free school zone law. The expansive geographic range of these zones, coupled with high urban density, disproportionately affects residents of urban areas—particularly people of color living in high-poverty areas. 22

Similarly, sentencing “enhancements” imposing longer prison terms for gang affiliation disproportionately affect Black and Latinx individuals. There is evidence that police and prosecutors are more likely to label people of color as gang members than whites in similar situations. In California, for example, over 90% of people who received a gang “enhancement” were Black or Latinx in 2020. 23

Other sentencing policies also exacerbate disparities. Lawmakers and practitioners often use criminal histories as a basis for requiring pretrial detention, for imposing prison instead of probation sentences, as well as for imposing longer prison sentences, which exacerbates disparities for Black Americans because they are more likely to have criminal records. 24 “Three strikes and you’re out” and other habitual offender laws, for example, reflect this pattern. 25 In addition, researchers examining sentencing guidelines have noted that Pennsylvania recommends “sometimes months or years more prison time” based on criminal histories and that criminal histories account for half of the racially disparate sentencing recommendations for the same offense in Kansas and Minnesota. 26

Programs offering alternatives to incarceration such as diversion programs and problem-solving courts also show the disparate impact of relying on criminal histories. These programs, such as drug, mental health, domestic violence, and veterans treatment courts, disproportionately bar people of color from alternatives to incarceration because they frequently disqualify people facing felony charges and with past convictions. 27

Growing public outcry combined with analyses of racial disparities at various stages of the criminal legal system have led lawmakers and criminal legal leaders to identify and mitigate several sources of racial inequity. As discussed in installment two of this series, several jurisdictions have limited police contact by removing police from low-level traffic enforcement, reduced drug arrests, and implemented alternative first responder models. 28 As noted below, other reforms are reducing the duration of punishment, revising laws and policies known to produce disparate outcomes, as well as anticipating them going forward—though not without significant pushback.

Lawmakers and prosecutors have begun pursuing reforms that reflect a key fact: ending mass incarceration and tackling its attendant racial disparities requires scaling back long sentences. 29 In 2018, California’s legislature empowered district attorneys to request resentencing for people whose continued imprisonment is no longer in the interest of justice. 30 Illinois, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington State also allow prosecutor-initiated resentencing. 31 In 2020, Washington, DC, passed the Second Look Amendment Act, expanding prior reforms to allow people who have served 15 years for crimes committed under age 25 to directly petition the courts for a second look at their sentence. 32 As part of an ambitious criminal code reform overhaul in 2023, the DC Council unanimously created a universal opportunity for resentencing after 20 years of imprisonment. 33 The bill, however, was vetoed by the mayor and, following the Council’s override, blocked by a bipartisan congressional resolution of disapproval signed by President Joseph Biden. 34 DC Mayor Muriel Bowser then introduced legislation whose provisions included limiting existing resentencing opportunities. 35

In 2014, Mississippi legislators reformed the state’s “truth-in-sentencing” requirement for violent crimes, reducing the proportion of a sentence that individuals with certain violent convictions have to serve before becoming eligible for parole from 85% to 50%. 36 Unfortunately Tennessee’s legislature has moved in the opposite direction, expanding its “truth in sentencing” law to require some individuals to serve 100% of their sentences. 37

The Death Penalty Information Center notes that “thirty-seven states—nearly three-quarters of the country—have now abolished the death penalty or not carried out an execution in more than a decade.” 38 In 2018, Washington State became the 23rd state to abolish the death penalty after the State Supreme Court unanimously overturned the law due to its racial bias. 39

In North Carolina, the Racial Justice Act (RJA) of 2009 enabled commutation of death sentences based on statistical evidence that race impacted sentencing. Four death sentences were commuted to life without parole. But in 2013, the legislature repealed the law. However, in 2020, North Carolina’s Supreme Court blocked the retroactive application of the repeal, protecting the rights of over 100 death-sentenced people to continue litigating RJA claims filed before the repeal. 40

Jurisdictions have made an effort to reduce sentencing disparities by repealing laws with racially disparate outcomes. In 2018, Congress passed the First Step Act, which included the retroactive application of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010’s reduction of the crack and powder cocaine sentencing disparity from 100:1 to 18:1. In 2022, the Department of Justice enacted a charging policy designed to prospectively eliminate this disparity during the Biden administration, to the extent possible absent a statutory change. 41 But Congress has yet to pass the EQUAL Act, which would enshrine this reform into law and apply it retroactively. 42 States like California, Connecticut, and South Carolina have equalized penalties for crack and powder cocaine. 43

Indiana amended its drug-free school zone sentencing laws in 2013 after the state’s Supreme Court began reducing harsh sentences imposed under the law and a study revealed its negative impact and limited effectiveness. The reform reduced drug-free zones from 1,000 to 500 feet, eliminated them around public housing complexes and youth program centers, and added a requirement that minors must be reasonably expected to be present when the underlying drug offense occurs. Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Tennessee have also amended their laws. 44

California lawmakers have limited gang “enhancements” by narrowing which crimes can serve as proof of gang activity. 45 A recent bill to increase penalties for gang-related crimes and gang recruitment, Senate Bill 2868, failed to win approval in a Mississippi Senate Committee in part due to concerns about its disparate racial impact—though the state’s existing gang law still stands. 46 In 2021, Virginia discontinued its use of GangNet, a database of nearly 8,000 alleged gang members across the region, after advocates voiced concerns about its overrepresentation of people of color. 47 Four out of five people in the database were Black or Latinx, raising questions of racial profiling and erroneous gang classifications across the database’s construction.

Two jurisdictions have re-examined their risk assessment instruments (RAI). A review of the RAI used in pretrial release decisions in Minnesota’s Fourth Judicial District helped reduce sources of racial disparity. Three of the nine indicators in the instrument were removed because they did not predict pretrial offending or failure to appear in court but were correlated with race. 48 New York City updated its RAI’s release assessment, which expanded pretrial release and reduced racial disparities in detention. 49 RAIs and other evaluatory methods could be further reformed with a reduced reliance on criminal history assessments. Pennsylvania’s sentencing commission has proposed scaling back the impact of criminal histories on sentencing guidelines, and Washington’s commission has considered similar reforms. 50

Problem-solving courts offer another way of reducing incarceration, when they are designed to divert prison-bound individuals rather than expose others to the possibility of incarceration. Some courts have begun expanding their eligibility criteria to include people who are determined to be higher risk based on risk-need-responsivity assessments, which often allows for the inclusion of people with criminal histories. In New York, the Manhattan Felony Alternative to Incarceration Court follows this model, ensuring those often rejected by other diversion programs are provided a crucial network of support and services, regardless of their offense or history. 51 In California, Proposition 36 mandated drug treatment instead of incarceration for people with up to two drug possession convictions, reducing the racial and ethnic disparities in access to diversion. 52

Ensuring future laws do not succumb to similar racial biases requires the widespread use of racial impact statements. Analogous to fiscal impact statements, racial impact statements are a tool for lawmakers to evaluate potential disparities of proposed legislation prior to their adoption and implementation. Nine states—Iowa, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey and Virginia—have implemented mechanisms for creating racial impact statements; in addition, the Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission creates racial impact statements and Washington, DC, officials established an equity impact statement policy. 53 In Iowa, this process was found to have helped to defeat some bills that would have exacerbated disparities. 54 Nicole D. Porter of The Sentencing Project testified in support of such a measure: “To undo the racial and ethnic disparity resulting from decades of punitive policies, however, states should also repeal existing racially biased laws and policies. The impact of equity impact laws will be modest at best if they are only prospective.” 55

States including Utah, Connecticut, Oklahoma, Alaska, and California have reduced prison admissions with “de-felonization” statutes that downgrade drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor. 56 In California, this reform led to steep declines in drug felony arrest rates, and narrowed racial disparities. 49 In Oregon, Measure 110 made the state the first in the nation to decriminalize the possession of controlled substances such as cocaine and heroin. The law also seeks to provide public health resources for those struggling with substance use such as drug treatment, housing assistance, and other behavioral health resources. 58

The movement to eliminate, shorten, or bypass mandatory minimum sentences has also helped to moderate criminal penalties disproportionately levied against people of color. Many states have repealed certain mandatory sentencing laws, and, along with the federal government, they have shortened mandatory sentences or created safety valve provisions. 59 Jurisdictions around the country have also made sentencing guidelines advisory rather than mandatory, empowering judges to customize sentences to the facts of the case. 60

But momentum for these reforms has stalled amidst the growing opioid crisis. Studies confirm drug criminalization as a failed harm reduction strategy, yet recently proposed legislation aims at increasing penalties for drug offenses. 61 For example, Congress’s Halt All Lethal Trafficking of Fentanyl (HALT) Act would increase the potential for incarceration and impose mandatory minimums for offenses involving fentanyl and its derivatives. 62 Many states have also bolstered their drug-induced homicide laws, broadening criminal liability for fatal overdoses among those who share drugs socially. 63 Further, Oregon’s delayed rollout of treatment services as part of Measure 110 has led to calls for the law to be repealed and has elicited concerns from some states considering similar reforms. 64

While most white Americans no longer endorse overt forms of prejudice associated with the era of Jim Crow racism—such as beliefs about the biological inferiority of Black people and support for segregation and discrimination—a nontrivial proportion, including those in law enforcement, continue to express negative cultural stereotypes of Black people, including stereotypes of criminality. 65 Implicit racial bias—unintentional and unconscious racial biases that affect decisions and behaviors—is pervasive among white Americans, and affects many people of color as well. 66 These biases are held even by people who disavow overt prejudice.

Studies of criminal legal outcomes reveal biased decision making in the work of police officers, prosecutors, judges, correctional officers, parole boards, and other members of the courtroom work group. One factor driving these outcomes is the paucity of people of color in these professional roles. Increasing the representation of communities of color among criminal legal professionals is necessary, but insufficient, for ending injustice. As the Center for Policing Equity has noted, “Law enforcement policies, procedures, and culture…are shaped by White supremacy. Any [police] officer working in such a system risks finding themselves engaged in behavior that is racist in nature, even if they do not, personally, hold racist beliefs or are themselves, Black.” 67

Prosecutors are more likely to seek imprisonment and to secure longer prison sentences for people of color than whites for similar crimes. Federal prosecutors, for example, have been twice as likely to charge African Americans with offenses that carry mandatory minimum sentences than whites with similar offenses and criminal histories. 68 Although prosecutorial practices are often opaque at the local level, a growing commitment to transparency, particularly among reform-oriented prosecutors willing to share data with researchers, has provided a better understanding of disparities in many jurisdictions. Charging disparities for similar crimes in Massachusetts have increased the likelihood that Black and Latinx people are directed to Superior Court than whites, where the available sentences are longer than in District Court. 69 Prosecutors in Ann Arbor, Michigan, brought more charges and secured more convictions per case for people of color than whites, contributing to their acquiring a “habitual offender” status and facing harsher future treatment in the courts. 70 More broadly, state prosecutors have been more likely to charge Black than similarly situated white defendants under habitual offender laws. 71 Prosecutors in Chicago, Jacksonville, Milwaukee, and Tampa have also been less likely to divert Black and Latinx individuals from felony charges than their white counterparts, in a pattern that offense severity, criminal history, and age do not explain. 72 Black people in Denver have been less likely to benefit from deferred prosecution, and controlling for factors including case severity and age did not eliminate the difference. 73 Researchers have also documented disparities in plea deals in jurisdictions such as Wisconsin. 74 By allowing this scrutiny of their work, many of these prosecutorial offices are making it possible to craft appropriate reforms to tackle sources of disparity.

Prosecutorial discretion also tends to disadvantage Black individuals both in early stages of criminal legal processing—jury selection—and in later stages involving parole consideration. As Wake Forest Law Professor Ronald Wright has observed about North Carolina, prosecutors’ peremptory challenges, in which they reject prospective jurors without explanation, are “a vehicle for veiled racial bias that results in juries less sympathetic to defendants of color.” 75 California prosecutors have also been more likely to oppose parole release for Black versus white and Latinx individuals, after controlling for differences in factors such as age, commitment offense, criminal history, and educational attainment. 76 More broadly, line prosecutors often espouse a racially-colorblind approach to their work, which is often contradicted by the results of their work and “perpetuates inaction in the face of racial disparities” 77 by failing to mitigate upstream disparities. In addition, some view their punitiveness as beneficial to Black defendants and their communities. 78

Further, prosecutors help to write the laws that they enforce. Many district attorney associations lobby, litigate, and engage in public advocacy against reforms that might lessen racial disparities, and oppose the work of reform-oriented prosecutors. 79 “American prosecutors are active lobbyists who routinely support making the criminal law harsher,” writes Carissa Byrne Hessick, the Ransdell Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina. 80 Her team’s 50-state study found that between 2015 and 2018, state and local prosecutors were involved in more than one-quarter of all criminal-justice-related bills and were nearly twice as likely to lobby in favor of a law that increased criminal penalties or added new crimes than for bills that might narrow the scope or punitiveness of criminal law. In 2019, 95% of elected prosecutors were white, with 73% being white men. 81

In 2016, 80% of state trial judges were white, in contrast to 30% of the defendants whose cases they oversaw. 82 Moreover, 18 states have no supreme court justices of color. 83 Studies that account for differences in crime severity and criminal history show that judges have been more likely to sentence people of color than whites to prison and jail and to give them longer sentences. 84 In federal court, the sentencing disparities between noncitizens and citizens are even larger than those across race. 85 In research from the Northeast and news coverage of Florida, judges expressed some willingness to mitigate their own biases, but little will to use their discretion to address disparities caused by other criminal legal professionals or by laws with a disparate impact. 86

Biased reactions by correctional officers to the behaviors of incarcerated individuals leads to racial and ethnic disparities in prison discipline, including in disciplinary write-ups that can lead to placement in solitary confinement 87 and later disadvantage people of color in parole hearings. 88 There is also evidence of racial bias in discretionary parole decisions after controlling for factors such as rehabilitative efforts, crime of conviction, and disciplinary history. 89 Parole boards rely on their own subjective assessments of candidates’ remorse and insight, a decision-making process prone to cultural and racial bias. 90 In fact, in light of parole boards’ unwillingness to release qualified individuals, legal experts such as the American Law Institute call for abolishing these entities and relying on judicial authority for release decisions. 91 Probation and parole supervision officers are also more likely to conclude that people of color, compared to whites, have violated the terms of their community supervision, triggering their imprisonment. 92

People of color are underrepresented in juries across the country, 93 which studies show produces bias in outcomes. Racially diverse juries deliberate longer and more thoroughly than all-white juries, and studies of capital trials have found that all-white juries are more likely than racially diverse juries to sentence individuals to death. 94 A study in Florida found that all-white jury pools convicted Black individuals 16% more often than whites. 95 Studies of mock jurors have even shown that people also exhibited skin-color bias in how they evaluated evidence: they were more likely to view ambiguous evidence as indication of guilt for darker skinned suspects than for those who were lighter skinned. 96 Defense attorneys may also exhibit racial bias in how they triage their heavy caseloads and struggle to gain some disadvantaged clients’ trust. 97

This section presents reforms to mitigate racial bias in prosecutorial decisions and across the criminal legal system, including jury deliberations and parole hearings.

Three states have addressed the role of peremptory challenges in limiting jury diversity. First, Washington State’s Supreme Court adopted a rule in 2018 expanding the prohibition of race-based peremptory challenges to include “implicit, institutional, and unconscious” bias. 98 Two years later, California’s legislature shifted the burden of proof for peremptory challenges: the state now requires attorneys who remove a prospective juror to prove that the cause was not race or other prohibited factors. 99 And finally, following a state Supreme Court ruling acknowledging their role in discriminatory jury selection, Arizona became the first state to eliminate peremptory challenges in 2022. 100

Prosecutors themselves have begun reforming charging decisions in some jurisdictions. To address the disproportionate prosecution of African Americans in San Francisco, prosecutors in 2019 tested out the process of “race-obscured charging” by concealing race and related information. 101 In race-obscured charging, prosecutors have access only to the reason a person was stopped, evidence that the person committed a crime, and witness accounts. They access all other information after making their initial decision. The Yolo County District Attorney followed suit in 2021 and led the California legislature to mandate this reform statewide by 2025. 102 But because the decision of whether to bring charges may not be a key site of bias within a particular jurisdiction, prosecutors’ offices should prioritize data collection and transparency so that reforms can be tailored to local drivers of disparities. 103

For over a decade, the Vera Institute of Justice has worked with prosecutors around the country to tackle racial disparities. In Milwaukee, Vera found that prior to 2006, prosecutors filed drug paraphernalia charges against a greater proportion of Black than white defendants. 104 The prosecutor’s office was able to eliminate these disparities by reviewing data on outcomes, encouraging diversion to treatment or dismissal, and requiring attorneys to consult with supervisors prior to filing such charges.

More recently, Vera’s Motion for Justice initiative has recommended that prosecutors presumptively exclude all consideration of criminal histories from charging, diversion, and sentencing decisions. 105 Prosecutors in Los Angeles and Alameda counties revised their offices’ charging practices, amidst strong resistance from the Los Angeles prosecutors’ union and Alameda County staff prosecutors, so as to not trigger California’s three-strikes law. 106 Researchers have also found that in Florida, prosecutors’ willingness to offer plea deals below sentencing guidelines for those with prior convictions contributed to Black decarceration outpacing white decarceration. 107

Reform-oriented prosecutors are also taking on extreme sentencing more broadly. In 2021, over 50 elected prosecutors joined in a statement issued by the organization Fair and Just Prosecution, calling for office policies “whereby no prosecutor is permitted to seek a lengthy sentence above a certain number of years (for example 15 or 20 years) absent permission from a supervisor or the elected prosecutor.” 108 To curb excessive penalties resulting from plea deals, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner has instructed his office to generally make plea offers below the bottom end of the state’s sentencing guidelines. 109

Vera also advises that prosecutors “advocate against state statutes that call for more punishment based on prior criminal contact, such as three strikes sentencing and habitual offender “enhancements,” or that indirectly exacerbate prior criminal contact issues by targeting Black and Latinx people, such as drug-free zone laws.” 110 In recent years, some reform-oriented prosecutors have left their state district attorney associations due to their anti-reform positions. In addition, many have partnered to advance reform through organizations such as For the People and Prosecutors Alliance of California. 111 For example, over 60 reform-minded elected prosecutors and law enforcement leaders working with Fair and Just Prosecution have called for second look legislation, and several have launched sentence review units. 112

While many cities are electing, and reelecting, reform-oriented prosecutors, these officials face substantial backlash. 113 A well-funded campaign led to San Francisco voters recalling District Attorney Chesa Boudin in 2022 and a campaign is underway to remove Alameda, CA DA Pamela Price. 114 In Los Angeles in 2022, DA George Gascón survived his second recall attempt in as many years with both efforts failing to gather enough signatures to make it on the ballot. In Philadelphia, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania rejected attempts to impeach District Attorney Larry Krasner, finding no legal basis for his removal. 115

Some Republican governors and lawmakers are also taking aim at prosecutors elected in their Democratic-majority cities. In 2023, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp signed a bill to create a commission with the power to oversee, discipline, and remove prosecutors elected in the state. Sherry Boston, DeKalb County DA, said this legislation “is not just an assault on prosecutors. It is an assault on our democracy.” 116 In Florida, Governor and 2024 presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis has removed two prosecutors: Andrew Warren was removed in Tampa due to his pledge not to prosecute people who seek or provide abortion or gender transition treatments and Monique Worrell was removed in Orlando for her office’s criminal charging decisions. Lawmakers across the country are similarly attacking prosecutorial independence with efforts disproportionately targeting black female prosecutors. 117

Several jurisdictions have worked to increase the diversity of jury pools and to mitigate bias among jurors. Federal and New York state courts are transparent about how the racial and ethnic composition of their jury pools compares to their broader communities—a critical step for achieving diverse jury pools. 118 The Iowa Supreme Court has ruled that courts must use more rigorous tests to determine whether the racial composition of juries meet the constitutional right to an impartial jury. 119

Mock jury studies have shown that increasing the salience of race and making jurors more conscious of their biases reduces biased decision making. 120 The practices of U.S. District Court Judge Mark W. Bennett when he was on the bench presents one model. He spent 25 minutes discussing implicit bias with the potential jurors in his court. 121 He showed video clips that demonstrate bias in hidden camera situations, gave specific instructions on avoiding bias, and asked jurors to sign a pledge to address their biases. The Iowa Supreme Court now also strongly urges judges to instruct jurors to not be swayed by racial bias in reaching a verdict. 122

In some jurisdictions, judges can now use their discretion to correct racial and ethnic injustices in sentencing. Both California and Utah now also allow people to seek resentencing if they can demonstrate that bias affected them. California’s Racial Justice Act allows people to ask the courts to vacate a conviction or sentence by proving with a preponderance of the evidence that an attorney, police officer, juror, judge, or expert witness exhibited bias or used discriminatory language about their race, ethnicity, or national origin. This includes showing evidence of racial disparities in charges, convictions, or sentences. 123 Likewise the Utah Sentencing Commission approved revisions to that state’s sentencing guidelines allowing defendants to argue that racial, ethnic, or other biases—whether conscious or unconscious—can be considered as a mitigating factor. 124

To reduce subjective parole release determinations—which are often politicized and laden with bias—states are increasing evidentiary standards for parole boards, creating presumptive parole policies, and developing objective criteria. In 2018, Michigan passed the Objective Parole law, which requires the state’s parole board to adhere to a set of objective, evidence-based guidelines. 125 Idaho, Massachusetts, Missouri, and the federal parole system also use a “clear and convincing evidence standard,” which raises the necessary burden of proof for denying parole. 126

New York’s legislature, courts, and governor have demanded that the state’s parole board give greater weight to how candidates have changed, to reduce their focus on the underlying offense, and to record their decision-making process. 127 In 2021, Maryland joined most other states (with California being among the notable exceptions) in ending gubernatorial reviews of parole decisions for people serving eligible life sentences. 128

Finally, New York and North Carolina require their parole boards to publish race, age, and other demographic data related to parole outcomes—a critical component of uprooting disparities. 129 Alabama and Alaska also make this information available. 130

“Agencies enjoying good reputations in the law enforcement profession and in their communities also benefit from larger, more diverse applicant pools,” 131 reports Governing, suggesting a virtuous cycle between representation and justice. Increasing the representation of people of color among law enforcement and courtroom professionals requires reforms including improving K-12 civics education, creating mentorship programs for attorneys of color, and increasing outreach efforts to attorneys from diverse backgrounds to pursue judicial careers. 132 The Supreme Court’s July 2023 ruling striking down affirmative action in college admissions highlights the urgency in safeguarding these equitable hiring practices and ensuring diversity and representation among criminal legal professionals. 133

Formerly incarcerated individuals are also beginning to enter elected office and criminal legal agencies. In 2020, Washington State elected its first formerly incarcerated individual, Tarra Simmons, to the state legislature and the New York State Assembly similarly made history in 2022 with the election of Eddie Gibbs. 134 Joel Castón became the first person to be elected to office in Washington, DC, while incarcerated: he won a seat on his Advisory Neighborhood Commission in 2021. 135 Rhode Island’s state legislature currently has two formerly incarcerated representatives: Leonela Felix and Cherie Cruz. 136 In addition, Minnesota recently mandated the inclusion of a directly impacted individual on the Sentencing Guidelines Commission and, in 2019, the Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor’s office hired two formerly incarcerated individuals as Commutations Specialists for the Board of Pardons. 137

Tarra Simmons is a member of the state House of Representatives in Washington’s 23rd Legislative District. Photo credit: Washington State Legislative Support Services.

Eddie Gibbs represents the 68th district in the New York State Assembly. Photo courtesy of the office of Assemblymember Gibbs.

Cherie Cruz (left) and Leonela Felix (right) are state representatives in the Rhode Island House of Representatives for the 58th and 61st districts, respectively. Photo courtesy of Leonela Felix.

Joel Castón served as an Advisory Neighborhood Commissioner in Washington DC while incarcerated at the DC Jail. Photo courtesy of Joel Castón.

Key segments of the criminal legal system are underfunded or are biased against people who are poor. With Black Americans earning half as much as white Americans annually and having one-seventh their average net worth, 138 criminal legal laws, policies, and practices that disadvantage people with limited income and assets disproportionately harm this population and other communities of color. Posting bail, hiring an experienced defense attorney, securing transportation for parole supervision requirements, obtaining support for substance use treatment, ensuring a successful reentry process, and countless other hurdles all place an outsize burden on lower-income individuals. In this way, the criminal legal system exacerbates society’s inequalities and lends to the over incarceration of people of color.

Pretrial detention largely affects people with limited financial resources. Of the 636,000 individuals confined in jails at year-end 2021, nearly three-quarters were unconvicted, having been detained prior to the resolution of their case. 139 With over a third of jailed individuals earning less than $10,000 in the year before arrest, cash bail requirements are often onerous. 140 People who remain in jail while grappling with a criminal charge are more likely to accept less favorable plea deals, to be sentenced to prison, and to receive longer sentences. 141

In addition, the risk assessment tools used in pretrial release and bail determinations often reproduce our systems’ preexisting racial inequities. They are typically based on criminal histories, employment, and socioeconomic status, and are validated using arrest data that are infused with racial bias. This ensures that people of color are more likely than whites to be held pretrial. 142

Case outcomes are closely tied to one’s access to high-quality legal representation. Four out of five defendants rely on publicly financed attorneys but most states inadequately fund their indigent defense programs, leading to unmanageable workloads that disadvantage those who rely on a public defender. 143 With public defenders’ excessively high caseloads and insufficient resources, indigent clients face longer detentions as they await representation and often are not provided a strong and meaningful defense against the superior resources of the prosecution. 144 Access to high-quality legal representation also affects prison release outcomes. In California, in 2021, candidates who were represented by state-appointed attorneys were granted parole at about half the rate of those represented by private attorneys. 145

Substance use disorder is a critical issue affecting many justice-impacted individuals. Nearly half of people in U.S. prisons had a substance use disorder in the year prior to their admissions, and many people—especially people of color—struggle to access drug treatment programs in communities and in prisons. 146 In 2021, over one-third of Americans with a substance use disorder did not seek out professional treatment because they lacked health care coverage or could not afford the cost. 147 In prisons, only about one quarter of those with substance use disorders receive any professional treatment. 148 In addition, the cost of diversion programs that help people access drug treatment and avoid incarceration is often prohibitive. 149

Likewise, for the 3.7 million people on probation or parole, community supervision serves as a “trip wire for further criminal legal system contact,” rather than a source of transitional support for rejoining the community. 150 Few people on community supervision receive guidance in accessing supportive services such as transitional housing or vocational training, while most face “prolific and suffocating” conditions of supervision, including the prohibition of alcohol use and contact with others who have a criminal record. 151 Similarly, reentry programs are underfunded and struggle to provide community and social services that can help address the health, employment, housing, and skill development needs of returning citizens. 152

The criminal legal system as a whole also disadvantages populations with limited English proficiency (LEP). Translation services are underfunded and courtroom staff lack training on how to provide adequate access to information and program assistance for LEP persons. Language barriers can lead to victims failing to report crimes, cases taking longer to process, police officers misleading the accused of their rights, and people staying in jail longer. 153

The criminal legal system can reduce disadvantages for low-income people of color by decriminalizing poverty, reforming onerous supervision practices, and limiting financial hurdles. Resources can instead be diverted to adequately fund public defense and social services. A number of jurisdictions have undertaken this task to date.

The former District Attorney of Suffolk County, MA (which includes Boston) limited her office’s use of criminal sanctions and either dismissed, declined to prosecute, or diverted people charged with nonviolent misdemeanors like disorderly conduct and shoplifting. Subsequent rearrests declined for those impacted by the reform and crime rates for nonviolent misdemeanor offenses did not increase. 154 The reform also prompted assistant district attorneys to consider alternatives to criminal adjudications that focus on substance use and mental health treatment. Recent research has found that charging individuals for non-violent misdemeanors increases their likelihood for future offending. 155 Refraining to pursue misdemeanor charges prevents the stigmatizing and often lifelong effects of a criminal record. 156

Lawmakers in Manhattan and Baltimore initiated similar reforms. 157 A study of Baltimore’s reforms to eliminate criminal penalties for certain offenses revealed no uptick in crime, a less than 1% rearrest rate for serious crimes among those impacted, and a disproportionate reduction in Black Baltimorians arrested. 158 Despite this success, the new State’s Attorney, Ivan Bates, has reversed this policy and ordered law enforcement to begin levying citations for “quality of life” offenses such as dirt bike riding, loitering, panhandling, public intoxication, and simple drug possession. 159

Measures to increase pretrial release have been relatively widespread at state and local levels. For example, lawmakers and practitioners in Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Philadelphia, Harris County, TX, and Los Angeles County have launched efforts to reform their bail systems to eliminate the role of income and wealth in jail incarceration for unconvicted individuals. 160 However, efforts to falsely tie these reforms to upticks in crime, opposition from the bail bond industry, and the failure of news media to offer clarity in these debates have contributed to a loss of momentum and rollbacks of some reforms. 161

The federal public defense system demonstrates the high quality of representation that is possible when indigent defense is adequately funded. 175 The Urban Institute has found that federal public defenders achieved a lower likelihood of incarceration and shorter sentences for their clients than private attorneys or Criminal Justice Act panel attorneys who are contracted by the government. 176

Judges have responded to evidence supporting properly funded indigent defense in some cases. A Cole County, MO, judge found the state’s waitlist for attorneys unconstitutional in 2023, ruling that counsel must be appointed within two weeks of defendants’ request. 177 The NY-ACLU sued New York State, demanding it aid counties in funding public defenses. This eventually led to budget negotiations that secured $250 million in annual funding for public defense services beginning in 2023. 178 Following a class action lawsuit targeting Oregon’s failure to provide representation, lawmakers released $100 million in emergency funding to address their defender shortage. 179 More recently, the state passed SB 337 which will restructure the Oregon Public Defense Commission to help enforce standards of representation and provide increased funding for public defense services. 180

Some federal lawmakers have also acknowledged the need to fund indigent defense on the 60th anniversary of Gideon v. Wainwright, which established the right to public defense but not funding for it. In March 2023, Senators Cory Booker and Richard Durbin introduced the Providing a Quality Defense Act to secure access to counsel regardless of wealth. The bill provides grants for public defenders to hire case support, promotes pay parity between public defenders and prosecutors, and more. In addition, the senators’ Sentencing Commission Improvements Act would elevate public defender perspectives by adding a new member to the U.S. Sentencing Commission with a public defense background. 181

As another approach to improving defense services, The Bronx Defenders is pioneering holistic defense, wherein they partner with social workers and community advocates to provide comprehensive defense and reentry support that addresses the underlying needs that led to an offense. 182 A study comparing the Bronx Defenders to another public defense organization found the holistic model’s focus on advocacy and communicating underlying circumstances and needs to judges helped reduce the likelihood of a jail sentence and sentence length. 183

Tribal Defense Offices (TDOs) have brought holistic defense to indigenous communities. TDOs partner with substance use treatment specialists, housing authorities, and community mentors to assist clients and those affected by an offense. 184 The Flathead Reservation Reentry Program in Montana 185 connects TDOs clients with tailored resources vetted by cultural committees to support reentry. 186 Similar practices have been launched by the non-profit Partners for Justice, which has implemented its “collaborative defense” model in 24 locations across the country. 187

Community supervision—including parole which follows incarceration and probation which is often in lieu of it—compounds the struggles low-income individuals face when rejoining their communities, by misdirecting resources into supervision that sets them up for failure and reincarceration, rather than providing them with support needed to thrive.

In California, lawmakers limited parole supervision for low-level offenses and funded evidence-based interventions that support treatment and reentry needs for supervised individuals. 188 These efforts led to a 36% decrease in the state’s prison and community supervision population between 2007 and 2020. 189 In his 2020 budget, Governor Gavin Newsom helped further these reform efforts by capping parole supervision terms of qualifying individuals at two years, with the potential for earlier release. 190

New York has implemented a suite of reforms. The New York City Probation Department enrolls its low-risk clients in less intrusive supervision that involves reporting to electronic kiosks monthly. 191 The city requires officers to submit requests for their early release from supervision for all individuals who meet reporting standards. 192 The program has been a clear success, in that those released early from probation had a lower reconviction rate than those who completed their full probation terms. 193 In 2022, New York State implemented the Less Is More Act, which allows people to be discharged from parole supervision early for good behavior and ends automatic incarceration after a reported violation. 194 The population of those in New York jails for technical parole violations in 2023 is an eighth of what it was prior to these reforms. 195

Allegheny County, PA, has also reduced its jail incarceration rate by ensuring that incarceration for probation violations is a last resort. When individuals are put in custody, new policies establish shorter holding periods and mandate parole officers to immediately implement a release plan. 196

To ensure fairness for U.S. residents with limited English proficiency, whose population has dramatically grown over the last 25 years, The Department of Justices’ actions to enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act have compelled states including Rhode Island to provide free court interpretation services. 197

Reforms across the last two decades have helped reduce overall levels of criminal legal system contact and have addressed key drivers of racial disparity. Even still, the crisis of mass incarceration and racial injustice persists and we are at risk of losing momentum and reversing hard-won reforms.

As this report has highlighted, jurisdictions around the country have begun tackling three key drivers of racial disparity: disparate racial impact of laws and policies, racial bias in the discretion of criminal legal professionals, and resource allocation decisions that disadvantage low-income people. But this progress is incomplete and under attack.

The next and final installment of the One in Five series will examine the criminal legal policies that exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities and the reforms correcting this final source of injustice.